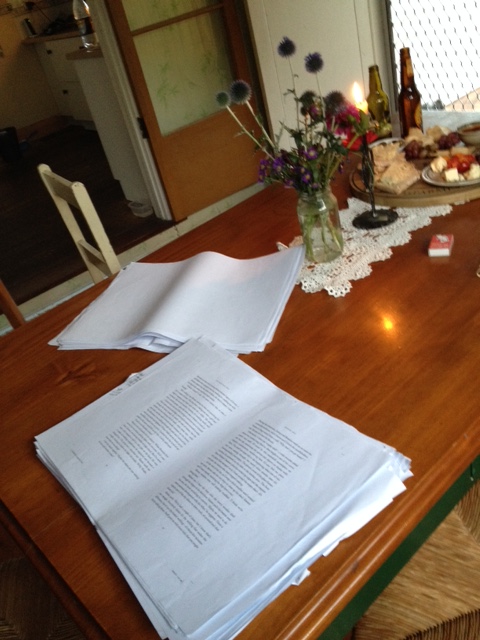

On the 25th August, Wild Boys was officially launched at the BackTrack Shed by Professor Annabelle Duncan, the Vice-Chancellor of the University of New England. The launch was an exciting day for me … the public acknowledgement of years and years of hard work was very affirming, and what follows is the gist of the speech I gave that day.

Many years ago, when an early chapter of Wild Boys was published in Griffith REVIEW, Bernie Shakeshaft said to me: ‘How lucky are we that you came down to the shed.’ At the time, my response to him was: ‘How lucky am I that I came down to the shed’, and even though writing Wild Boys has involved a significant amount of personal sacrifice and hardship, I can still say: ‘How lucky am I? I got to be part of something – a whole other world – that not many women experience, and I learned a lot about life in the process.

One of the unexpected outcomes of writing Wild Boys is my ongoing affection for the BackTrack boys – both past and present. I’ve come a long way since my first day at the shed – when I rocked up, full of nerves, to find Bernie driving out the gate, saying: ‘I’ll be back soon… just go inside and meet the boys. They’ll show you around.’ It’s fair to say I was completely out of my comfort zone that day, but I soon realised that there was nothing to fear.

Like many things in life, we fear what we don’t know, and fear and prejudice usually arise from ignorance – from not understanding and not being able to feel empathy towards a group of people who are different to you. Part of the reason why I wrote Wild Boys was to provide an insight into the ‘wild boys’ in our community – to shine a light on what it is to be a teenage boy who, for various reasons, struggles at school and can become known as a ‘loser’ early in life, simply because he doesn’t fit the system. That’s a pretty harsh judgement for a society to make upon a young person, so I wanted to write something that would influence the way people think and feel about wild boys, something that might encourage them to care more and judge less.

Recently, I helped set up the school program at the shed, and I got to know some of the boys who are currently at the shed. One day, we had to go somewhere for lunch on the spur of the moment, so I said to the boys, ‘Let’s go to my house and have a BBQ there.’ When we reached my house, the boys jumped out of the troopie and dashed off to the backyard – where they started making a BBQ and cutting up onions and chopping wood and fixing the back fence and cutting back all the overgrown bushes in my garden.

I remember some people were surprised to hear I’d invited the boys back to my house that day, but I didn’t see any problem – because once again, there was nothing to worry about. Those boys were so generous with their help, and open and friendly – just as they’ve always been with me. I’m not at the shed much these days, but one of the joys of my life is when I’m downtown and I hear someone call out: ‘Hey, Helena!’ and I turn around and it’s one of the BackTrack boys. For some reason, that simple exchange always makes me feel like the world is becoming a better place.

The story of the seven original BackTrack boys who feature in this book is very moving. Yes, there’s a lot of swearing, and a few times where the boys lose their way. But when they were given help to get back on track, those boys made the choice to accept that help and move ahead in life – to rise above the trajectory that was set out for them and to emerge as winners, to become known as the ‘Magnificent Seven’ – and that was a wonderful thing to witness. At the back of Wild Boys is a section where those seven boys share the lessons they learnt from their time at the shed. It’s only recently that I’ve been able to read this section without becoming very emotional because the responses are so deep – so beautiful – and this is from a group of boys who, for the most part, struggled at school and were often in trouble with the police.

That’s why the BackTrack shed is so special – it gives young people who don’t fit the system a place to shine, where they too can emerge as winners in life. It’s like one of the boys says at the end of the book: ‘Everyone needs to find a place … and from there you can grow. The shed gave us that place.’

So, how lucky am I that I got to see all that happen – and to write about it so that others can also experience the beauty of what goes on down here and understand how positive change comes about in a community. Along with documenting the early days of BackTrack, Wild Boys also describes how Bernie helped me through a pretty challenging time in my life. I never expected to write about myself in this book, but, really, once I started coming along to the shed, there was no way that I was going to come out the other side of this experience without my life being transformed in some way because that’s what happens here – people’s lives are transformed.

I used to rely on Bernie’s help quite a lot, but he’s a good mentor – a good teacher – because I hardly ever need to ring him now. I still run into troubles, of course, but mostly, instead of ringing Bernie for help, I go back and think of the lessons I’ve learnt in the past – and how I can apply that knowledge to the current situation I’m struggling with. Many unique ‘Bernie-lessons’ are in the book – and I’m sure others will find them just as useful as I did.

Like I said, I don’t get down to the shed enough these days – I’m like the dog that runs along the outside of the pack – but I think I will always carry the experiences I’ve had at this shed close to my heart, especially some of those times with the BackTrack boys.

![Boys, Bernie, Annabelle and Helena[1]](http://www.helenapastor.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Boys-Bernie-Annabelle-and-Helena1-1024x684.jpg)

![Crowd1[2]](http://www.helenapastor.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Crowd12-1024x623.jpg)